Reanimating the Past: Sergei Iukhimov's Bridge of Khazad-dûm

The following piece is an excerpt from a much larger research project involving Sergei Iukhimov's illustrations for the 1993 TO Izdatel' edition of Natalya Grigor'eva and Vladimir Grushetskij's translation of The Lord of the Rings (Властелин Колец).

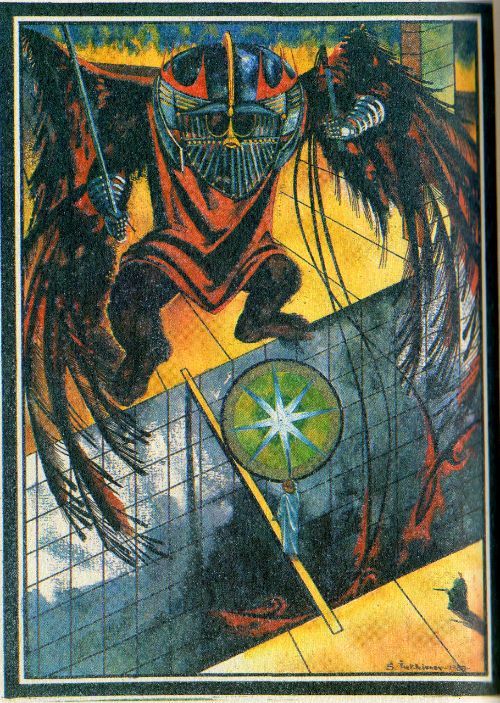

Flames feature once again in Volume I. II. Plate 8. Bridge of Khazad-dûm (Мост Казад Дума Most Kazad Duma, 1988), in this instance forming the backdrop to the climactic scene from Book Two Chapter V of The Fellowship of the Ring where the Balrog (meaning "Demon of might" in Sindarin)[1] confronts Gandalf on the "slender bridge of stone" spanning "the chasm near the eastern gates of Moria.[2] Tolkien describes the creature’s reaction to Gandalf’s initial challenge as follows,

…suddenly it drew itself up to great height, and its wings were spread from wall to wall; but still Gandalf could be seen, glimmering in the gloom; he seemed small and altogether alone: grey and bent, like a wizened tree before the onset of a storm.

Grigor'eva and Grushetskij’s encounter is similar in content, however they immediately assign the Balrog a gender, something which Tolkien (as narrator) does not.[3]

He took a step and suddenly grew, filling the full volume of the mountain hall. The darkness in his wings thickened and stretched from wall to wall. The small, shining figure of Gandalf stood alone against the backdrop of a rolling storm cloud.[4]

Iukhimov’s portrayal of the scene encompasses many of the most important elements; the Balrog is armed with blade and whip (although not a flaming blade, as in the original description); its form is huge and dark, and fire rises from a fissure in the "smooth floor" of the chamber behind it.[5] Iukhimov’s bridge is depicted, correctly, as being too narrow to be crossed save in single file and Gandalf bars the way with his sword Glamdring shining brightly in his hand. The wizard’s apparent human frailness in the face of the Balrog is effectively conveyed, and the nimbus of light around the sword points to both the blade’s Gondolin origins and Gandalf’s own divine power as a Maia. There are discrepancies, however. As a structure, the bridge appears a good deal shorter and more rectangular than Tolkien’s "curving spring of fifty feet."[6] To Gandalf’s right, at the edge of the chasm, there stands a hobbit with a sword (possibly Frodo), whereas in Tolkien’s text only Aragorn and Boromir held their ground at the eastern end of the bridge.[7] The most contentious feature of Iukhimov’s image, however, must surely be the Balrog’s wings; or more pointedly, the validity of Iukhimov employing an obviously figurative (albeit elaborate and ornamental) component to illustrate what, in fact, could be a purely metaphorical descriptive detail. His inclusion might well resonate with Grigor'eva and Grushetskij’s description, where the Balrog advances towards the bridge with its "two wings of darkness" flung open behind it.[8] But Tolkien himself was more ambiguous in his wording. If his bridge scene were to be taken literally, then indeed, the textual Balrog would appear to possess actual wings. However only two paragraphs prior to this description, Tolkien writes, "His enemy [the Balrog] halted again, facing him [Gandalf], and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings [my emphasis]."[9]

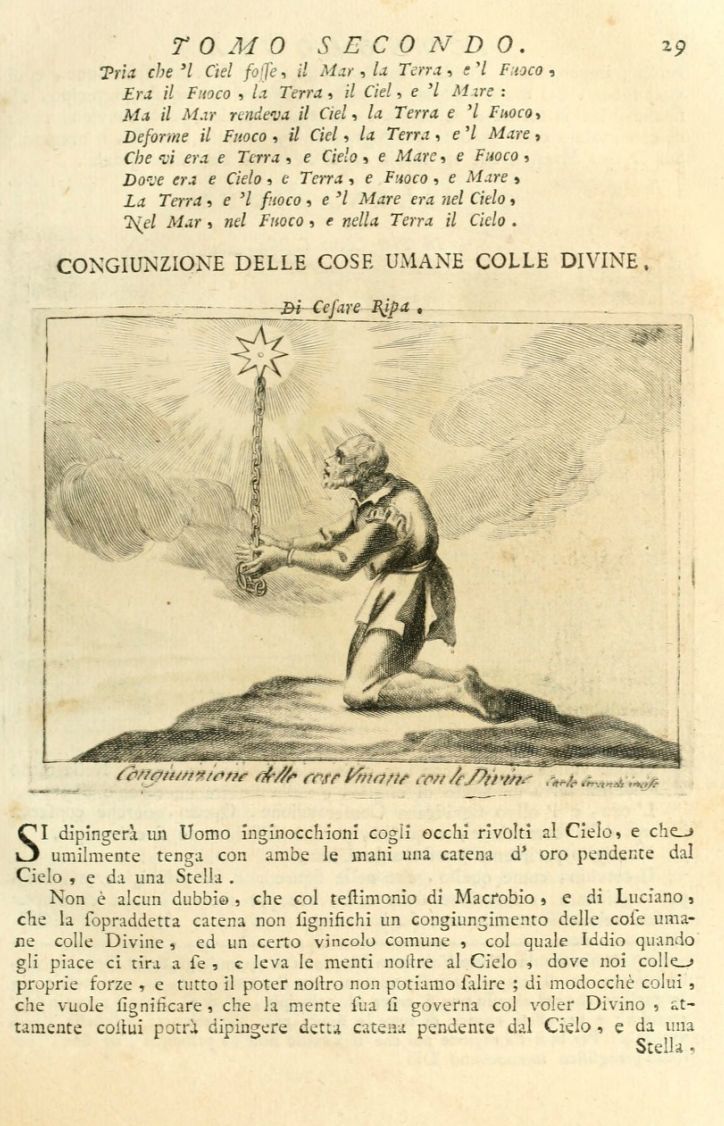

The overall composition of Bridge of Khazad-dûm does not appear to be derived from any direct visual prototype. Unlike many images in the corpus, the design displays a strong three-dimensional element, with the geometric lines of the stone floor, chasm and bridge helping to channel the gaze towards the Balrog. Outside of the Balrog, the focal point of the illustration is the eight-pointed star, or octogram, emanating from the tip of Gandalf’s sword Glamdring. Compositionally, this feature forms both an inner core around which the Balrog’s wings and whip thongs curl, and a counterbalance to the creature’s helmeted head. It is also meaningful from an iconographic perspective as the eight-pointed star has often been considered (in Christian art), a symbol of, to quote Carman, "regeneration and divine inspiration".[10] Particularly salient in this regard (at least as far as the Glamdring octogram is concerned) is an illustration from Volume II page 29 of Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (below) which depicts a kneeling man clutching a vertical length of chain connected to a shining eight-pointed star in the sky overhead. Underneath the illustration there is the telling caption, Congiunzione delle cose Umane con le Divine ("The Conjunction of Human things with the Divine").

Interestingly, Iukhimov’s Balrog wears an ornate helmet complete with mask and cheek-guards, something which would make it considerably difficult for the creature to breathe fire through its nostrils.[11] This helmet design itself appears to have a direct visual prototype in the early 7th century iron and bronze Anglo-Saxon helmet discovered in 1939 as part of the Sutton Hoo ship burial excavation.[12] As an artefact, the original helmet (below) suffered considerable damage whilst still underground, possibly as a result of a collapse in the burial chamber, and therefore has been reconstructed several times since its excavation (the most recent effort being in 1970-71).[13]

Among the most notable features which have survived are the bronze-gilt winged dragon motif which forms the eyebrows, nose and mouth pieces of the helmet, and the downwards facing serpent’s head which comprises part of the iron crest ruuning from back to front.[14]

An examination of the helmet on Iukhimov’s Balrog reveals a very similar design, which, although lacking the actual dragon heads of the Sutton Hoo prototype, visually corresponds to the geometric pattern of the original motif. The roundness of the eye holes on the Balrog helmet design has been accentuated, and a gilt edging added which, although missing from the original damaged Sutton Hoo helmet, can be viewed on the early 1970s Royal Armouries complete reconstruction (detail below) which was created for (and now displayed at) the British Museum (Fig. 51.). This version of the helmet had been extensively photographed prior to 1988 (when Iukhimov painted Bridge of Khazad-dûm) and showcases the complex array of figural scenes and zoomorphic interlacing which would have decorated the original Sutton Hoo artefact. The small, radiating interlace panels which adorn the top and bottom section of the Royal Armouries face mask, plus the horizontal band which separates the two, is reflected, in a simplified form, on the corresponding section of the Balrog’s helmet.

The original helmet was found in Mound 1 of the Sutton Hoo site, to the left of the (presumed, as no body was found) final resting place of an East Anglian, or possibly East Saxon king, who had lain undisturbed for over twelve hundred years.[15] The Balrog of Moria, Durin’s Bane, had itself remained "hidden at the foundations of the earth since the coming of the Host of the West" and it was only by the delving of the Dwarves in Moria that it was brought to the surface.[16] It is not infeasible therefore, that the conflation of these two motifs; the iconic symbol of the ancient king whose grave has been uncovered, and the Balrog figure roused from its subterranean rest might evoke a strong intertextual message: the long buried warrior-kind have returned.

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, 382.

[2] J.R.R. Tolkien. The Fellowship of the Ring, 329.

[3] As Christopher Tolkien confirms in The Treason of Isengard, p206, from the earliest drafts of the encounter, the Balrog had always been referred to as ‘it’. Later, however, in The Two Towers, Book III Chapter V, The White Rider Gandalf (when relating his tale of the Battle of Zirakzigil) repeatedly refers to the Balrog as "him" or "he".

[4] J.R.R. Tolkien, Vlastelin Kolets I, 273.

[5] Two trolls had just bridged the fissure with stones, however the Balrog had simply leapt across. See J.R.R. Tolkien. The Fellowship, 343.

[6] J.R.R. Tolkien. The Fellowship of the Ring, 329.

[7] J.R.R. Tolkien. The Fellowship of the Ring, 330.

[8] J.R.R. Tolkien, Vlastelin Kolets I, 273

[9] J.R.R. Tolkien. The Fellowship of the Ring, 330.

[10] Charles H. Carman, "Cigoli’s Annunciation at Montughi: A New Iconography," The Art Bulletin 58, no 2 (1976): 220.

[11] J.R.R. Tolkien. The Fellowship of the Ring, 330.

[12] J. D. Richards, "Anglo-Saxon Symbolism", in The Age of Sutton Hoo: The Seventh Century in North-Western Europe, ed. M.O.H. Carver (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1992), 131.

[13] Rupert Bruce-Mitford, The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume 2: Arms, Armour and Regalia. (London: British Museum Publications, 1978), 138.

[14] Rupert Bruce-Mitford, The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume 2, 169.

[15] Michael Parker Pearson, Robert van de Noort and Alex Woolf, "Three Men and a Boat: Sutton Hoo and the East Saxon Kingdom", Anglo-Saxon England 22 (1993): 50.

[16] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King, 1072.